Last month, I posted an article titled “MBTI Types and Their Finances: What Do We Know.” This article described how an individual’s personality type (nature) contributes to their attitude towards personal finances. This theory emphasizes that the financial decisions we make are a result of our nature. But could they actually be a result of our environment (nurture)? Or perhaps, a little of both (nature and nurture)? This is a reflection of the age-old question in psychology: Are people a result of their nature or nurture (Cherry, 2019)?

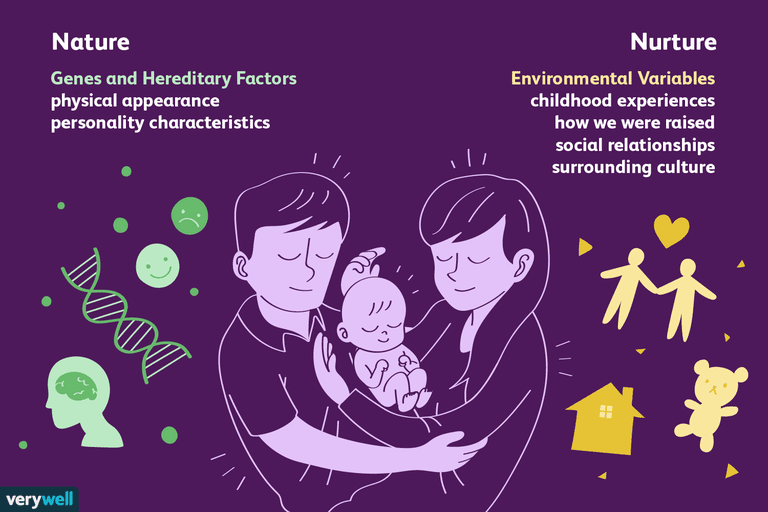

By definition nature refers to all the hereditary factors that make up who we are such as physical appearance and personality (Cherry, 2019). Nurture, refers to the environmental variables that impact who we are such as upbringing, relationships, and culture (Cherry, 2019).

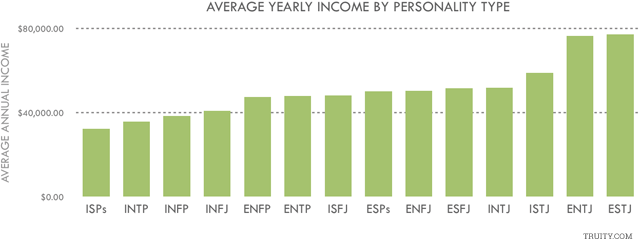

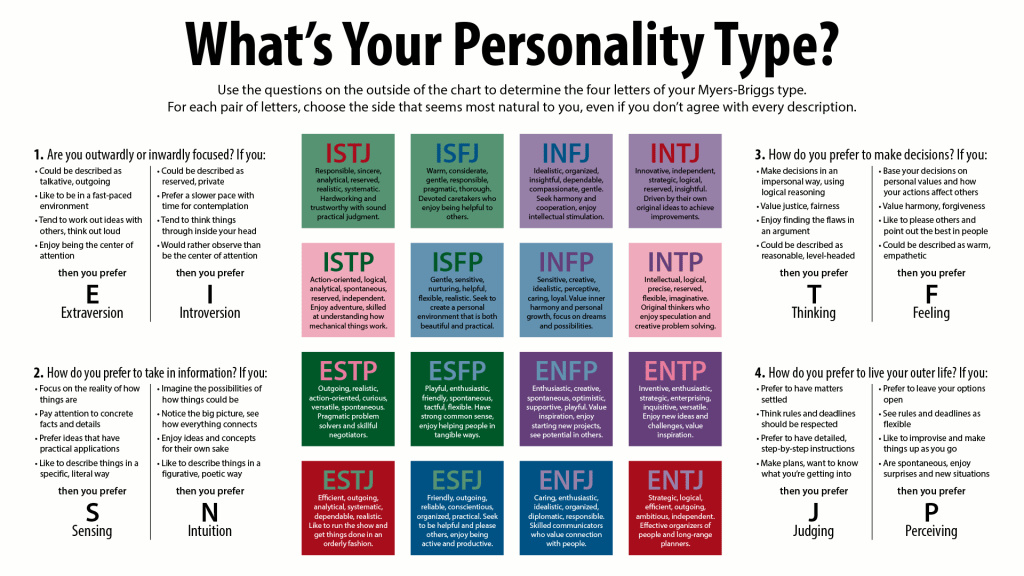

In regard to personal finances, our nature could play a significant role in the decisions we make. As outlined in the previously mentioned article, “MBTI Types and Their Finances: What Do We Know” that are four categories of financial decision makers. These categories are based upon each MBTI personality type and their expected approach to personal finances. A summary of each category can be found below:

- Protectors (ESTJ, ESFJ, ISTJ, ISFJ): By nature, protectors (who make up 38% of the population) are very conservative with their finances (Keyishian, 2020). “They think ahead, make sure their future is taken care of, buy the same brands, and shop at the same stores” (Keyishian, 2020, para. 8).

- Planners (ENTJ, ENTP, INTJ, INTP): Those who fall within this category are future-focused and tend to concentrate on long-term investing. Planners (who make up about 12% of the population) succeed at evaluating risks and creating contingency plans (Keyishian, 2020).

- Pleasers (ENFJ, ENFP, INFJ, INFP): Pleasers (who make up about 12% of the population) tend to take their finances very personally. Those who fall within this category view money as an extension of themselves. Therefore, how they spend it is an expression of their identity (Keyishian, 2020).

- Players (ESTP, ESFP, ISTP, ISFP): Players (who make up about 38% of the population) are among the personality types with the highest financial risk (Keyishian, 2020). Characterized as compulsive and carefree, these personalities can end up in financial ruin if they are not cautious.

Our nurture can also play a significant role in the financial decisions we make. Nurture is a bit different from nature in that it is continually evolving (Barrington, 2010). Our nature does not change, whereas our environment (nurture) is constantly changing (Barrington, 2010). Therefore, if nurture affects our attitude towards personal finances, this attitude can actually change throughout our lives as we have different experiences (Barrington, 2010). For example, if a child is raised in an environment in which their parents are frivolous with money, their childhood and teenage years may be defined by an apathetic attitude towards personal finances. However, when this child becomes an adult and is suddenly faced with adult financial responsibilities (student loans, a mortgage, bills, investing, saving, etc.) they may become more conservative with their finances. Our relationships can also play a role in our financial decisions (Barrington, 2010). If we are friends with people who spend a lot of money, we will likely spend a lot of money too (at least when we are with them). However, if we are friends with people who prefer to save or invest their money as opposed to spending it, we will be more inclined to do the same.

So the question remains: are our financial decisions a reflection of our nature or nurture? As contemporary psychology suggests, it is probably a little of both. As stated in the previous example, people who are friends with spenders instead of savers, have an increased chance of also being a spender. However, if your nature inclines you to save, you may choose to only be with your spender friends when spending money is not involved. For example, instead of going out to eat with these friends, you may suggest going for a hike instead.

It is important to note that psychologists are beginning to realize that asking how much nature or nurture influences a particular trait is not the right approach (Cherry, 2019). The reality is, there is no way to disentangle the myriad of forces that exist (Cherry, 2019). These forces include genetic influences that interact with one another, environmental influences that interact, and the interactions of both hereditary and environmental influences (Cherry, 2019).

In the end, it does not matter whether nature or nurture determines our financial decisions. As humans, we still have the power to make our own decisions despite our genetic makeup or environment (Barrington, 2010). Through self-determination, we can still break bad spending habits, learn to invest, and increase our savings (Barrington, 2010).

References:

Barrington, R. (2010). How nature vs. nurture impacts your spending habits. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/nature-nurture-and-saving_b_751780?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAMxzwpr9HlkTR0KSfmF09Iq-3nW0PKseEqvAOZ5xGy0YNR3ABZUADiogDTmjUFL2C-oBU58wAMGPFAH4KNmx5yoKHCFdtwslEjmNLU9zJEAcSvMmD5RIlStuvfJFh2OoJCGjhHkklDn4UmrrYRdN-tDqgVnbziSqEjeb4nRby0Fm

Cherry, K. (2019). The age old debate of nature vs. nurture. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-nature-versus-nurture-2795392

Keyishian, A. (2020). What your personality type means for your finances. Retrieved from https://www.themuse.com/advice/what-your-personality-type-means-for-your-finances

Image References:

Keyishian, A. (2020). What your personality type means for your finances. Retrieved from https://www.themuse.com/advice/what-your-personality-type-means-for-your-finances

South-East Timber and Damp, LTD. (2018). Baby-accountant. Retrieved from https://timberanddamp.co.uk/about-us-2/baby-accountant/