COVID-19 is a disease caused by a type of virus called a coronavirus (WebMD, 2020). A coronavirus is a common type of virus that can cause respiratory tract infections; however, most coronaviruses are not dangerous (WebMD, 2020). Following a December 2019 outbreak in Wuhan, China, the World Health Organization identified a new type of coronavirus. The new virus was: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This is the virus that causes COVID-19. By January, COVID-19 had quickly spread to the United States and other parts of the world. Like most other coronaviruses, COVID-19 spreads through person-to-person contact (WebMD, 2020). When an infected individual coughs or sneezes, they can spray droplets up to six feet away. Inhaling these droplets causes other to become infected with the virus. The virus can also be spread by touching a contaminated surface and then one’s face (eyes, nose, or mouth) (WebMD, 2020).

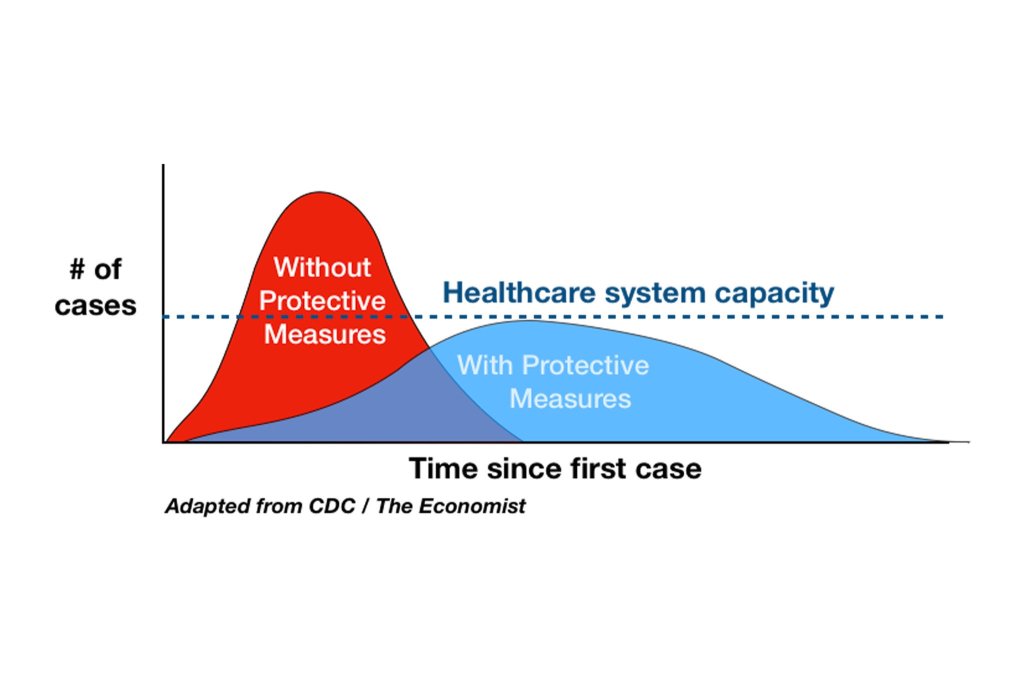

By the end of February, the first cases of community spread COVID-19 began to appear in the United States. “Community spread means spread of an illness for which the source of infection is unknown.” (Center for Disease Control, 2020, para. 2) The beginning of March brought forth increasing cases of the novel COVID-19. By beginning to mid-March, many schools, workplaces, and events began to undergo cancellations in an effort to flatten the curve. Flattening the curve refers to efforts to minimize the spread of a disease. This aids in not overwhelming health care facilities so current cases can be handled effectively (Roberts, 2020).

With cancellations and other restrictions on the rise, Americans began to become more anxious about the implications of a global pandemic. In the United States, customers began visiting stores and clearing the shelves. Toilet paper, paper towels, and hand sanitizer were all gone within days or even hours. Customers also began stocking up on other items such as nonperishables and staples like bread, milk, and meat. This type of purchasing behavior has been coined as panic buying (Wiener-Bronner, 2020). Panic buying is a type of herd behavior. In psychology, herd behavior refers to individuals in a group acting collectively without any centralized direction (Braha, 2012). In economics, panic buying is categorized under consumer behavior theory, the broad field of economic study dealing with explanations for “collective action such as fads and fashions, stock market movements, runs on nondurable goods, buying sprees, hoarding, and banking panics” (Strahle & Bonfield, 1989, p. 567). Overall, panic buying is a group action that tends to worsen as the group grows in size. Those who start panic buying ignite worry in a second tier of consumers who begin panic buying as well. This second tier of panic buyers then inspires a third tier to do the same. The cycle continues until the shelves are bare.

The implications of such buying practices effect both consumers and retailers. However, retailers are equipped to handle the surge in demand whereas many consumers are not. Supply chains are built to react to disruptions. “A bad crop yield or a factory fire could lead retailers to swap suppliers or turn to alternative products” (Wiener-Bronner, 2020, para. 12). Major supermarket chains and retailers are fortunate enough to have supply networks across the globe. If one supplier is experiencing shortages, they can turn to another (Wiener-Bronner, 2020.)

On the other hand, consumers may find themselves in a sticky financial situation due to panic buying. Reacting on immediate emotions of anxiety and panic, individuals may overextend themselves financially by maxing out credit cards, taking out high-interest loans, or overdrawing their bank accounts. This comes at a time when many consumers are already experiencing interruptions in income due to workplace closures. Filings for unemployment benefits are on the rise as many are losing hours or their job altogether (Schnieder & Zarroli, 2020). The Department of Labor stated, “a number of states specifically cited COVID-19 related layoffs, while many states reported increased layoffs in service related industries broadly and in the accommodation and food services industries specifically, as well as in the transportation and warehousing industry, whether COVID-19 was identified directly or not” (Schnieder & Zarroli, 2020, para. 4). The latest number for unemployment filings was an increase of 70,000 from the previous week. These numbers are expected to increase (Schnieder & Zarroli, 2020). In fact, several states reported that their unemployment claims websites had crashed due to so many people trying to file at once (Schnieder & Zarroli, 2020).

Overall, this is financially challenging time for many people. The results of panic buying could leave thousands of people with bills they simply cannot afford to pay. This issue is ongoing and only time will tell how, when, and if it can be resolved.

References:

Braha, D. (2012). Global civil unrests: Contagion, self-organization, and prediction.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048596

Center for Disease Control. (2020). CDC confirms possible instance of community spread COVID-19 in U.S. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/s0226-Covid-19-spread.html

Roberts, S. (2020). Flattening the coronavirus curve. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/science/coronavirus-curve-mitigation-infection.html

Schnieder, A., & Zarroli J. (2020). Filings for unemployment benefits rise as coronavirus hits job market. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2020/03/19/818234501/filings-for-unemployment-benefits-rise-as-coronavirus-hits-job-market

Strahle, W. M., & Bonfield, E. H. (1989). Understanding consumer panic: A sociological perspective. Advances in Consumer Research, vol 16.

WebMD. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/lung/what-is-covid-19#1

Wiener-Bronner, D. (2020). How grocery stores restock shelves in the age of coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/20/business/panic-buying-how-stores-restock-coronavirus/index.html

Image References:

Roberts, S. (2020). Flattening the coronavirus curve. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/science/coronavirus-curve-mitigation-infection.html

Savage, D., & Torgler, B. (2020). Here’s the difference between “panic buying” and reasonably preparing for a crisis. Retrieved from https://www.sciencealert.com/reasonable-preparations-before-a-crisis-isn-t-panic-buying-here-s-the-difference